Eutrapelian LandMinds

Thoughts on thoughts

Monday, July 28, 2025

Eutrapelian LandMinds:The Space Delusion: Why Humanity Isn’t Ready for Life Beyond Earth Humanity’s Space Obsession: A Symbol Without Substance? By Boris (Bruce) Kriger

The Space Delusion: Why Humanity Isn’t Ready for Life Beyond Earth

Eutrapelian LandMinds: What Was Scattered Was Not Destroyed By Colin Gillette for FRONT PORCH REPUBLIC

EUTRAPELIAN LANDMINDS

What Was Scattered Was Not Destroyed

Churches aren’t offering peace. They’re optimizing for engagement. And what gets built in the end is impressive. But like all “Babels,” it can’t bear the weight of the human soul.

Colin Gillette

July 22, 2025

for

Thursday, July 24, 2025

Eutrapelian LandMinds: From Blisters to Blessings: Why ordinary is the new radical: Losing track, meaningful pain, talking to strangers, and more... By Peco and Ruth Gaskovski

School of the Unconformed

From Blisters to Blessings: Why ordinary is the new radical

For those of you who prefer to read off paper rather than the screen, we have converted the post into an easily printable pdf file.

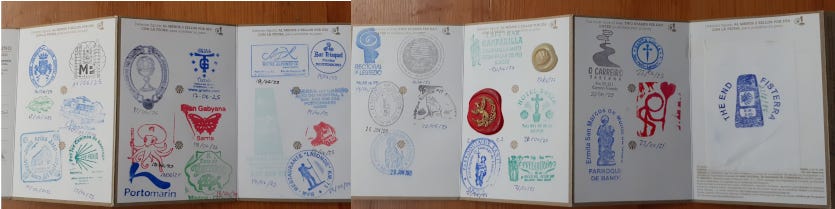

Minutes spent on internet: 0

News articles read: 0

Km walked: 117

Restaurants and cafés visited: approx. 30

Strangers turned into friends over eleven days: 22

We time-traveled with a group of radicals in Spain. Together we ambled on paths forged by Celtic tribes in search of the end of the world four thousand years ago, feasted on tables laden with jamón serrano, pulpo (octopus), and empanadas (introduced by the Visigoths), and prayed in a 9th century pre-schism church where St. Francis of Assisi once knelt.

A pilgrim we met along the way from England related how her young co-workers no longer had a notion of connecting with people in real life. Starting their days with swiping, working on screens all day long, only to return home to reels of other people living lives online1. We hear of twenty-somethings who long to have a family, who write to inquire how to live a “normal, grounded life”, and truly have no idea where even to start. How do you meet people? What do you talk about? What do you do?

We conceived of the 117 km journey we covered on foot as a pilgrimage “out of the Machine”, a sudden exit from lives dominated by screentime, sedentariness, and isolation, and a sunlit plunge into an embodied and human-centered experience. The ordinary yet ancient human rites of walking together, sharing meals, praying, talking for long hours—and suffering aches and pains together—cracked open doors to what one pilgrim expressed as “startling intimacy” with strangers.

It was a total mental and physical overhaul. We might be back “in” the Machine, yet the many lessons learned on the pilgrimage have followed us home, freshly inspiring us to shake off the shackles of unwanted technologies in our lives. We share here with you not just our experience, but offer a translation of Camino insights into everyday life.

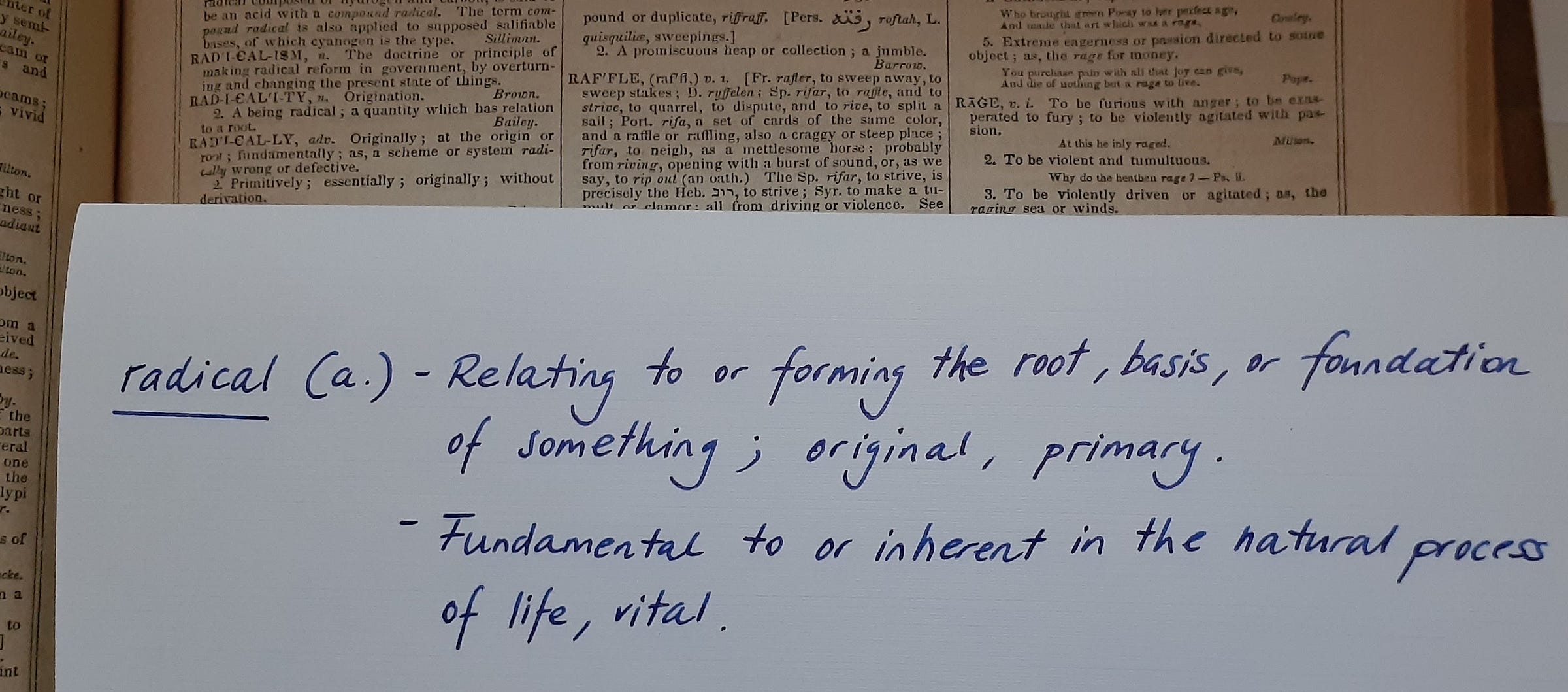

We hope that you too might feel prompted to commit yourselves to a simple truth: to be ordinary is to be radical.

Radical space, radical speed

It’s easy to underestimate how much time we spend in our heads. When looking at our smartphone screens, thinking we’re reading about something “out there” in the world, we aren’t “out there” at all, but “in here”, inside of our minds. Even when not on our devices, we are often in our heads, caught up in a mental swirl of thoughts and feelings.

Modernity encourages us to value our subjectivity above all else, to venerate our own headspace and the contents therein. It can be comfortable, but it’s also alienating. People might be sitting beside each other at a supper table, or on a bus, but staring into their screens, absorbed in different headspaces, lost in totally different universes. Households of parents and children can co-exist physically, yet have little in common.

Pilgrimage offers a cure for this alienation.

On the Camino, everybody walks the same road, mile after mile. We suffer the same blisters and sweltering heat. Most of the pilgrims in our group had phones, but they weren’t much used. Most of us, rather than being in a screen-based headspace, were in a different kind of space. A foot-space. A land-space. A conversational-space.

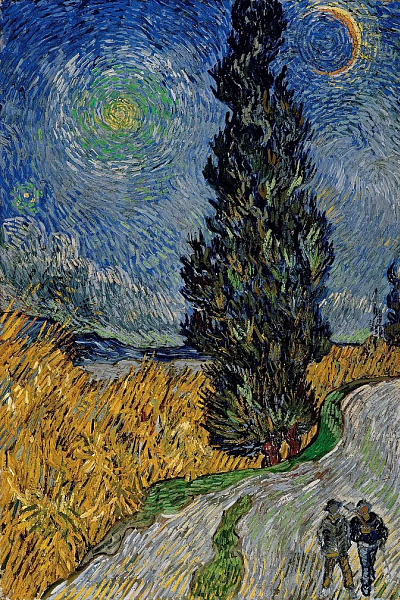

Screens pull you into an artificial reality, but pilgrimage pulls you out, and grounds you—literally. Each step anchors you to a particular spot on the earth, imprinting your footstep. It’s your momentary mark on the world. Forty-thousand momentary marks later, you are done.

The next day you do it again.

The world reveals itself to those who travel by foot.

-Werner Herzog

Speed affects how we see the world. At 3 mph, walking pace, we can better perceive our surroundings, have time to process what we observe, and carry on conversations. We think and talk more easily when walking. Time gets slowed down.

When the entire world seems to spin at 100 Mbps, walking is a radical speed. As one of our fellow pilgrims,

, observed, it’s a blessing…to spend several days in a row at a walking pace. Yes, it was hard, and painful too, but also good to see how most people in the history of mankind have traveled—at a walking pace. As I settle into this next stage of my life (in retirement), I have been praying that God would show me how best to use the time I have. I think a lesson from the Camino is that it’s okay to do life at a walk—it doesn’t have to be at 60 mph down the highway. And walking long distances means pacing myself if I’m going to finish the journey.

Losing track

T.S. Eliot’s J. Alfred Prufrock measured out his days in coffee spoons2, but the convergence of Wi-Fi, wearable tech, and GPS have sent us over the deep end in measuring and tracking our daily lives. Beyond counting steps, calories, and sleeping hours, iPhones can now track your mood, sexual activity, toothbrushing, hours spent in daylight—you name it, and it can be measured.

Teens share their location and keep track of each other in order to “to manage anxiety, track social dynamics and feel less alone.” Tracking offers the comfort of control, but can lead us into micromanaging our lives, leave us feeling like our own science experiment, and result in a never-ending loop of “anxiety, stress, and never being content.” And as one former self-tracker observed, “If you’re lost in life, you won’t find answers in the data you’re collecting…”3

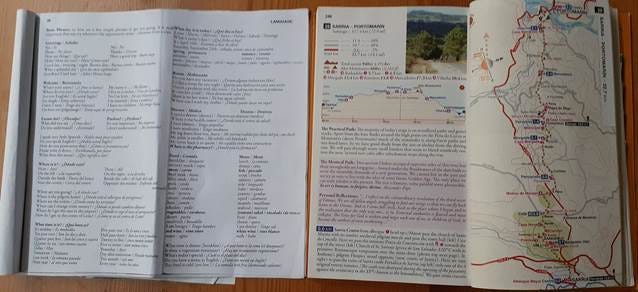

While some pilgrims did wear step counters, we all seemed to revert to an era of trust and proximal “sensing”. We often did not know our exact location, but used a simple paper map and the km marking stones to make our way. We did not keep track of each other’s location, but trusted that we’d all eventually arrive; and we did. Indeed, we were never quite sure where our three children (aged 13, 17, and 19) were, except that they were chatting with fellow pilgrims a few kilometers ahead or behind, and trusted that we’d encounter them at the end of the day.

captured the experience perfectly:You see, on the Camino, there is no map. I mean, sure, you can buy a map. But that’s not how this Way is navigated.

Instead, you step onto the path and then you simply follow it. Every once in a while you will see a marker with a shell and a yellow arrow directing you to turn. But that is your only guidance other than the movement of any pilgrims who may be visible in front of you (and let’s hope that they’re following the arrows!). You never know if you’re about to begin an ascent or a descent, about to switch to dirt or pavement, about to enter or leave a city or village or town or just walk all day on a sun-drenched dirt path with nary a cafe or fountain to be seen. If you’re hungry, you must wait for a cafe; thirsty, wait for a fountain; sore, wait for a place to soak your feet. Sometimes it comes and sometimes it doesn’t…

Your job is not to know the way, you see. Your job is only to walk and to follow the arrows when they appear and to take what comes to you for the gift that it is.

When we don’t know exactly where we are, yet trust the path, we can open ourselves up to surprise, curiosity, wonder. There is liberation in not having to monitor our location or activities, in freeing ourselves from obsessive metrics-checking, and instead having our full attention engaged in the moment.

One evening, Dixie and our older son sang a hymn by John Henry Newman before supper, reminding us that all we need to see is the step right in front of us:

Lead, Kindly Light, amidst th'encircling gloom,

Lead Thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home,

Lead Thou me on!

Keep Thou my feet; I do not ask to see

The distant scene; one step enough for me

No opting out

A man on a thousand mile walk has to forget his goal and say to himself every morning, 'Today I'm going to cover twenty-five miles and then rest up and sleep.

from War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

On a pilgrimage, there is no opting out. If you get tired of reading this article, you can click or scroll and look for something more interesting. The internet does not ask for your commitment. Our culture often encourages the implicit belief that nobody should be stuck doing anything that might bother or bore them for too long. The freedom to opt out, unsubscribe, get a refund, is a core value of the technological world.

Pilgrimage inverts this expectation. The path must be followed. There is simply no other way. There are side paths, of course, detours, different roads to Santiago, but you still have to walk (or bike, or wheelchair). People with serious injury or illness can skip parts, and yet, we observed that even partially injured people often felt compelled to keep walking, or limping.

A couple of days into the walk, our daughter got a touch of heat stroke. She had to cab the last kilometer to a hotel, and missed the rest of the day with a fever. Next morning, though still ailing a little, she was on the road again. She later said that if she had been even half as sick while at home, she would have skipped classes and spent the day in bed.

Often, when you can’t opt out of a difficult situation, you discover a resilience you didn’t know you had.

Meaningful pain

The pilgrimage, for all its ordinary blessings, might sound wonderful—and it was. But if we were to tell you that you would spend the next six days walking until your muscles ached, your feet throbbed, your body neared exhaustion, all while the sun burned down on you and made you yearn for an ice-cold drink, you might think that you’d have a miserable time ahead of you.

You might think that spending your days bathed in pleasure and comfort would make you happier. After all, who wants pain?

Yet our exposure to pleasure, if excessive, can backfire. As noted by Anne Lembke, author of Dopamine Nation, “with prolonged and repeated exposure to pleasurable stimuli, our capacity to tolerate pain decreases, and our threshold for experiencing pleasure increases.”

If you get too much pleasure, it’s harder to experience the sweetness of it; and if you don’t experience enough pain, even a little can seem worse than it actually is. Beyond that, a modicum of pain in life, in the form of daily struggle, effort, toil, boredom, might be precisely what makes our pleasures more pleasurable. Walk twelve miles in the hot sun, and even the simplest meal or cold drink becomes a quiet joy.

Our devices, so ingeniously designed to give us “frictionless” experiences, often leave us hollow and unhappy, precisely because they are effortless, struggle-less, diminishing our capacity to experience ordinary pleasures optimally.

Physical struggle and (a degree of) pain can also encourage much-needed self-reflection. Research on the psychological impact of the Camino revealed that it helped pilgrims to,

address their spiritual issues, set priorities, and learn the truth about themselves, often difficult and painful but usually liberating. They described this process as “removing the mask” or “removing the make-up.”…Thanks to the Camino, they were able to distance themselves from everyday life and observe the value of matters they had not appreciated previously. It was a time of struggle not only with their physical endurance but also with their own thoughts.

From pixels to portraits

When two people meet, each one is changed by the other so you've got two new people.

-John Steinbeck

On the final day of the pilgrimage, after we had reached the great cathedral in Santiago, many of us had to keep stretching and shifting our feet during the Mass to relieve the soreness. We had all pushed through some pain. It was, separate from any spiritual feeling, a source of unity. When people have gone through a struggle together, they relate better.

And deeper connections happened. Each of the pilgrims in our group had different motivations for signing up, some religious, some not. Yet despite these differences, something else emerged: a shared purpose. Our different headspaces, different universes, joined and overlapped.

Walking the path, day after day, had created a bond between us. How often, when we’re online interacting with “friends”, do we wish our connection was more than just digital? And we did not have to force it. We did not need to devise a gimmick or ideology to make it happen. It was the byproduct of what happens when human beings share a direction, and exert a common effort. Relationship plus sweat equals healthy society.

And walking a common path did not override our individual differences. The sameness of the experience did not make us all the same. It actually turned out to be a foundation in which we could see our differences more richly.

Our pilgrim group included people of different church denominations—Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant—and some who followed non-Christian spiritualities and philosophies. The youngest was 13, and the oldest were in their 70s. One pilgrim was surprised to discover how well he got along with another pilgrim, especially after learning they shared contrary political views. On social media, two people like this might be at each other’s throats within 280 characters.

Online, we don’t experience each other in the fullness of who we actually are, but simplified, abstracted, fragmented, curated. It’s little wonder our society has become so obsessed with “identity”; we are no longer complex individuals, to be discovered gradually over time through shared experiences in the real world. The online reality reduces us to a false theoretical essence: our political party, race, religion, sexuality, and other crude categories.

The pilgrimage, again, inverted this experience. Our abstract digital identities fell into the background, while our faces, our tone of voice, our gestures, our gait, the way we laughed, the stories we told—a more vivid image of our actual identities—came into the foreground. The pilgrimage turned us into portraits rather than pixelated representations and profile blurbs.

Talking to real people? Getting to know each other face-to-face? It might sound ordinary, but in a world where people are spending more and more time hanging out in isolated digital universes, ordinary is the new radical.

Talking with strangers

There are no strangers here, only friends you haven’t met.

(possibly) William Butler Yeats

We did not know any of the pilgrims who joined our group. In the beginning, they were mere names on a list, small icons on a screen; in the end, they had been incarnated into real people with rich and fascinating lives.

The openness that each of us brought on this journey made us fast friends seemingly overnight. One way of turning strangers into friends is to start with this conviction: there are no boring people. If we insist on seeing through our assumptions and outward surfaces, then we are bound to discover something wonderful in the newly-minted grandmother, or the 13-year old brimming with “punny” jokes, or the avocado farmer.

On the Camino, talking with strangers is a given. Everyone who passes by greets you with a “Buen Camino”, offers encouragement with a smile, and if walking at the same pace, is often quick to enter a conversation that can last from a few minutes to hours.

We asked our 13-year old how he struck up conversations with pilgrims along the way. He looked at us dumbfounded: “What do you mean how? You say hello, make a comment about what you see around you, or the weather, and then you end up talking about their grandkids, shark teeth, or why they like convertibles…”

Talking with strangers makes you happier, and not just on pilgrimage. Researchers Nick Epley and Juliana Schroeder invited commuters in Chicago to talk to someone on the train. Although participants had expected that it would be preferable to “sit in silence rather than talk”, they found that chatting with a stranger improved their mood. Even chatting with a barista at Starbucks, rather than just buying a coffee in silence, resulted in a better mood and greater feeling of connection.4

Prompted by these findings, Gillian Sandstrom created a “strangers’ scavenger hunt game”, which involved talking briefly with a stranger who matched a specific description (e.g. “someone wearing a hat”, or “someone drinking a coffee”). After a week of this, people felt more confident in their conversational skills, and less worried about rejection. Imagine a whole society encouraging more everyday contact between people, not with any ideological agenda, but just to encourage ordinary trust?

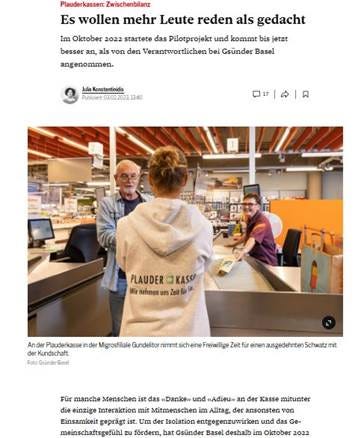

It’s actually happening in some places. Switzerland has introduced the opposite of self-checkout: The Plauderkasse or “chat-checkout”. Cashiers and “conversation volunteers” at this grocery checkout take time to personally connect with customers. It’s proven hugely popular, especially among seniors, and there are plans to expand the practice across the entire grocery store chain.

Meanwhile, the Swiss have also introduced the opposite of the dating app, “hiking instead of swiping”. Rather than meeting people online, why not climb a mountain with a group of eligible young men and women searching for a close relationship? It’s a bit like the Camino, just at higher altitude.

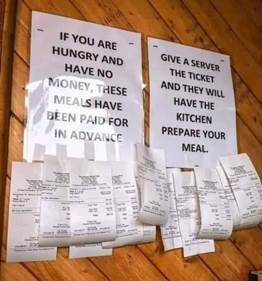

Generosity to strangers can also build trust. On the Camino, there’s a tradition, apparently originating in Naples, where people will pay ahead for a coffee or meal for anyone who can’t afford it. More than that, the Camino encourages a generosity of spirit between strangers: an openness to smile, to talk, to offer assistance if needed. Such small, humanizing acts cost us little time or money, but can be more meaningful than we realize.

The “ordinary” social reality of the Camino—sharing struggles, getting to know each other in person, acts of generosity—are available to all of us, all the time. They are not pilgrimage realities, they are human realities. They require effort, risk and vulnerability, and the practice of social skills. The result—to recall the words of one of our pilgrims—is “startling intimacy”.

The Ordinary Radical

Two years ago we introduced the 3Rs of Unmachining: recognizing the harms of technology, removing unwanted technologies from our lives, and returning to a more grounded way of living. Our pilgrimage was a microcosm of the 3Rs, as it took us out of our screen-dominated lives, away from social media, AI chatbots, and myriad online bubbles, and returned us to a simple, natural, relationship activity: walking on a spiritual path.

While the Camino is a Catholic pilgrimage5 to the tomb of St. James, the lessons of the pilgrimage are universal. There are religious rites, yet there are also human rites, ordinary things we have always done, and that we must keep doing, if we want to remain and grow as human beings.

Technology keeps trying to uproot the ordinary with promises to make it extraordinary. It replants us in a digital garden, but there, our roots wither as it is not our native ground. So we may feel isolated, anxious, empty, used, or distorted.

Our real home is out here, on real ground.

So be a radical: go for a long walk, push through the pain, lose track, don’t opt out, meet people face-to-face, talk to strangers. Embrace the ordinary.

We’d love to hear from you!

Please share your questions, thoughts, and reflections in the comments section!

Eutrapelian LandMinds:The Space Delusion: Why Humanity Isn’t Ready for Life Beyond Earth Humanity’s Space Obsession: A Symbol Without Substance? By Boris (Bruce) Kriger

EUTRAPELIAN LANDMINDS The Space Delusion: Why Humanity Isn’t Ready for Life Beyond Earth Humanity’s Space Obsession: A Symbol Without Subs...

-

Wouldn’t Let Go of Me John Jankowski · 50 I was raised Catholic in Chicago in a blue-collar family. My father was not religious, but my moth...

-

Carrier Stories I spent seven years working as a circulation manager of a local media company. My responsibilities included the contracting ...

-

61 and Counting Sixty-One and Counting A Morning of Acting One’s Ag e · Our little corner of the Driftless received some rain last night. Fi...