“Tomorrow, You’re Homeless. Tonight, It’s a Blast!”

Trump and the non-ideological wing of the protesters have at least one thing in common: a lack of faith. And that lack of faith drives them to create their own particular and specific idea of utopia or heaven here on earth.

Trump has obtained his (wealth and power) by way of corruption, and aims to keep it — by any means necessary. Same for his most powerful and wealthiest of supporters.

Rioters have neither the means nor the same ends as the filthy rich; but their demands for “a better future” are as real and as essential as Trump’s grip on wealth and power. Trump’s Bible-debasing and hate speech are signifiers of his true and only heaven on earth. Violence and outrage are those of the weak, whose heaven may only amount to the desire for a few crumbs from the rich man’s table. Rioting renders the formerly invisible, visible. The weak, powerful.

As Malcolm X once quipped regarding violence during the previous Civil Rights Era, “The chickens have come home to roost.” They most certainly have. And Trump is no farmer.

Riot

Song by Dead Kennedys ‧ 1982

Source: LyricFind

Songwriters: D.H. Peligro / East Bay Ray / Jello Biafra / Klaus Flouride

Riot lyrics © Kobalt Music

Rioting, the unbeatable high

Adrenalin shoots your nerves to the sky

Everyone knows this town is gonna blow

And it's all

Gonna blow right now

Now you can smash all the windows that you want

All you really need are some friends and a rock

Throwing a brick never felt so damn good

Smash more glass

Scream with a laugh

And wallow with the crowds, watch them kicking peoples' ass

But you get to the place

Where the real slave-drivers live

It's walled off by the riot squad aiming guns right at your head

So you turn right around

And play right into their hands

And set your own neighborhood

Burning to the ground instead

Ah, ha-ha

Ah, ha-ha

Ah, ha-ha

Ah, ha-ha

Riot, the unbeatable high

Riot, shoots your nerves to the sky

Riot, playing right into their hands

Tomorrow you're homeless, tonight it's a blast

Get your kicks in quick

They're callin' the National Guard

Now could be your only chance to torch a police car

Climb the roof, kick the siren in and jump and yelp for joy

Quickly, dive back in the crowd, slip away, now don't get caught

Let's loot the spiffy hi-fi store, grab as much as you can hold

Pray your full arms don't fall off, here comes the owner with a gun

Ah, ha-ha

Ah, ha-ha

Ah, ha-ha

Ah, ha-ha

Riot, the unbeatable high

Riot, shoots your nerves to the sky

Riot, playing right into their hands

Tomorrow you're homeless, tonight it's a blast

Yee-ah!

Yee-ah!

Yee-ah!

Yee-ah!

Yee-ah!

Shit!

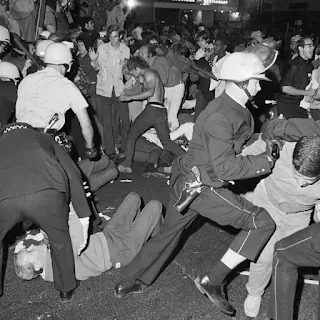

The barricades spring up from nowhere

Cops in helmets line the lines

Shotguns prod into your bellies

The trigger fingers want an excuse

Now!

The raging mob has lost its nerve

There's more of us but who goes first?

No one dares to cross the line

The cops know that they've won

It's all over but not quite, the pigs have just begun to fight

They club your heads, kick your teeth

Police can riot all that they please

Ah, ha-ha

Ah, ha-ha

Ah, ha-ha

Ah, ha-ha, yeah!

Riot, the unbeatable high

Riot, shoots your nerves to the sky

Riot, playing right into their hands

Tomorrow you're homeless, tonight it's a blast

Riot, the unbeatable high

Riot, shoots your nerves to the sky

Riot, playing right into their hands

Tomorrow you're homeless

Tonight it's a blast

Tomorrow you're homeless

Tonight it's a blast

Tomorrow you're homeless

Tonight it's a blast

Tomorrow you're homeless

Tonight it's a blast

Tomorrow you're homeless

Tonight it's a blast

Tomorrow you're homeless

Tonight it's a blast

Tomorrow you're homeless

Tonight it's a blast

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O69MTDdhHDk