Chasing the Ghost of Robert Johnson in the Mississippi Delta

By: Erik Rittenberry

Poetic Outlaws

Jun 15, 2025

“To understand the world, you must first understand a place like Mississippi.”

—William Faulkner

Sometime in my early 20s, I fell in love with that beautiful yet enigmatic sound of the BLUES.

As soon as I heard those painful wails from Son House and Howlin’ Wolf, and that mournful guitar playin’ of Robert Johnson, and that erratic cry of the harmonica by Little Walter and Sonny Boy Williamson, and that somber yet soulful voice of Bessie Smith, I was hooked for life.

It did something to the soul and I never did quite recover. I devoured all the books I could find about this raw art form. I read biographies, learned about the toilsome lives of these old bluesmen, and the place they came from.

The Mississippi Delta. I had to go and experience it for myself.

So here I am, torn Levis, battered soul, and that old trucker hat sittin’ loosely on my hungover head, cruising down legendary Highway 61 south out of Memphis with the windows down and the radio up as Jim Morrison wails those Roadhouse Blues.

The future is uncertain and the end is always near.

Those words bite deep. I’m in a mood, man, and I figure there’s nothing left to do but LIVE and let go of the grudges and seek out moments that set the core ablaze with ecstasy. That’s my aim.

With a full tank of gas, a light rucksack, and a styrofoam cooler of cold brews sloshing around in the trunk, I’m heading down to a barren place of grueling poverty and open skies to discover the music of it all.

I’m in the Mississippi Delta. Deep down in it. The most southern place on earth. It doesn’t take too long driving around here to realize that this is one of the few places left in this country unscathed by the gnarled appetite of modernity.

And I’m here for it.

It’s a place with excess crops and a grim past. A place where the sins of yesterday loiter in the soil and white-portico mansions sit majestically behind cotton fields that whisper untold truths.

I am here alone to wash away from the soul the “dust of everyday life.”

I want to breathe it in. Feel the purity of that southern wind roll across my skin. I want to wander under the ruthless sun and drift down deserted dirt roads. I want to talk to the people of this desolate land. Listen to the music. In the land of the Delta Blues, under the infinite skies, I want to be here, madly alive, living life like a poem.

My GPS guides me into that fine delta town of Clarksdale, Mississippi.

I open the weathered door to my rented shotgun shack in the middle of an old historic plantation and walk in to find quirky art and old photographs plastered on the plank walls. The rustic floors creak under my boots. A vintage radio in the back spews the blues. There’s no television. I throw my stuff inside, open a cold beer, and sit on the front porch that looks out over the endless fields.

I like people with grit and style; folks with dirt on their skin and blood in their spirit. People who live here seem to be emancipated from the ailments of corporate convenience. It’s a hard life for many, but genuine.

This is a place where old black men with somber eyes sip bourbon and sell fruit out of their vintage trucks on the side of the road.

A place where ebony queens and long-haired gypsies dance madly in one of the few remaining Juke joints left in this starving land.

A place of blooming magnolias, and dank bayous, and a sense of hard times in the closed, rundown shops everywhere you look.

In the words of Richard Grant: "It's why the Delta doesn't progress. It's not having anything, and not really wanting anything, because that would mean change. That would mean taking on more responsibility. Too many of our people are not interested in progress and change."

Anyway, I’m here to experience this forgotten place and to rage and to get a little taste of the Delta Blues — the most beautifully haunting sound the world has ever known.

The birth of the Delta Blues was the raw-edged, honest answer to years of poverty and oppression. It was a desperate sound that slithered out of the soil from the sweat, pain, and resilience of African Americans enduring the ruthless realities of sharecropping, Jim Crow oppression, and a life of relentless toil.

The Delta is a flat, fertile land of cotton plantations and soybean fields that stretches between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers. In the late 19th and early 20th century, formerly enslaved people and their descendants worked the land under brutal conditions. Sharecroppers labored long hours for meager pay, often trapped in debt to landowners. This hardship bred a raw, expressive music that captured the weight of survival. It was a melodic cry of defiance as a way to cope with their harsh realities.

As Kurt Vonnegut once wrote:

“…the priceless gift that African Americans gave the world when they were still in slavery was a gift so great that it is now almost the only reason many foreigners still like us at least a little bit. That specific remedy for the worldwide epidemic of depression is a gift called the blues.”

I down my beer and throw my rucksack in the back and drive off as the dirt and dust stir up a red cloud in my wake.

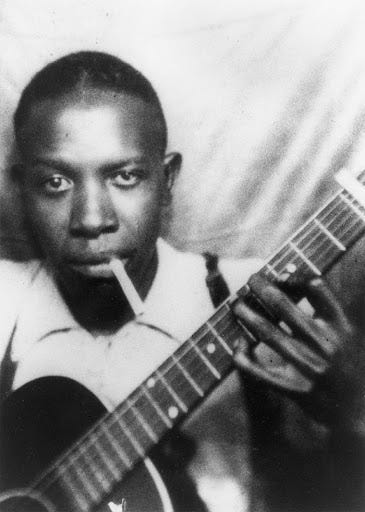

With the sun beating down, I arrive at an old church to look for the grave of famed bluesman Robert Johnson. He died before he was 30 years old. And we know very little about his life — a life heavily shrouded in mystery and folklore.

Born in 1911, Johnson grew up poor in the Mississippi Delta. He hated laboring in the fields and became captivated by the sound of the guitar. According to accounts of other bluesmen of the day, like Son House, he wasn’t any good. He was run out of bars and laughed at. But after a 6-month hiatus, Johnson returns with his guitar in hand from God knows where, and surprises the shit out of everyone with his incredible guitar skills.

It was out of this world.

Legend has it that he sold his soul to the devil at the Crossroads in exchange for the ability to play guitar, unrivaled. The old Faustian bargain.

Johnson became a big shot around the Delta. He was charismatic, talented beyond measure, a loner, and liked to sip a little whiskey and holler at the women.

One late summer night, as the moon hung high over the Delta, Robert was in an old Juke playing some tunes. Story has it that the owner of the place found out that his pretty little woman had been messin’ around with the slick bluesman. Overcome with jealousy and rage, the bar owner placed a poison-laced pint of corn whiskey in Johnson’s hand while he was on break. After Robert Johnson took a few strong pulls, he shortly became sick and died a few days later. He was only 27 years old.

When I arrive at his alleged resting place (no one knows for sure where he’s buried, but the general consensus among blues biographers points to Little Zion Missionary Baptist Church in Greenwood, Ms), I find a long gravel driveway leading up to a battered wooden church that sits in the shade of a massive pine. A small graveyard sits to the left. There is no one around. I am alone. And besides a subtle breeze that pushes through the trees, it is eerily silent.

I walk past a few gravestones before I find the obvious one that belongs to the dead bluesman. There is a beaded necklace draped from the corner. Cigarettes and bottles of whiskey decorate the base. Little notes were left behind by admiring fans. Some even left harmonicas and guitar pics.

Sitting there at the gravesite, I couldn’t help but go back two decades to when I first heard of Robert Johnson. I was reading Bob Dylan’s autobiography, Chronicles. Dylan, whom I’m a huge fan of, mentioned hearing Robert Johnson for the first time. He writes:

“From the first note the vibrations from the loudspeaker made my hair stand up. The stabbing sounds from the guitar could almost break a window. When Johnson started singing, he seemed like a guy who could have sprung from the head of Zeus in full armor. I immediately differentiated between him and anyone else I had ever heard.”

Damn. For Dylan to write these idolizing words made me beyond curious.

I had to hear this voice for myself. I went out and bought Robert Johnson’s ‘The Complete Recordings’ and threw it into my truck CD player. The sound I heard made the world throb around me. I heard something soul-piercing yet disturbing in these mournful wails, like hearing an uncomfortable truth for the first time.

This man was singing tales of no-good women and dread and falling into the clutches of evil. The clarity, the honesty, and the sheer enigma were ushered along with the punch of the guitar. My reality shifted at that point. I wanted to listen to more. I wanted to read about this voice and the place it came from and to try to understand the struggles and hardships that manifested such desperate pleas — such magic.

It was that voice that brought me to this moment. The breeze picked up and the sun dipped below the tree line. Alone, sitting at the stone sipping whisky, I hear the cry of Robert Johnson echo in the wind:

“You may bury my body, down by the highway side

(Baby, I don’t care where you bury my body when I’m dead and gone)

You may bury my body, ooh, down by the highway side

So my old evil spirit, can get a Greyhound bus and ride”

From there it was on to Red’s, one of the last authentic juke joints still around. It sits bruised and battered right in the heart of Clarksdale.

I roll up into the joint with an ass pocket of whiskey. There’s old bluesman playing tonight by the name of Watermelon Slim. I imagine this was what it must’ve been like when Robert Johnson was playing in the area back in the day.

The ambiance was nostalgic.

The bar sits untidily to the right as I walk in. It has a few cheap fridges where the beer is held. No liquor. No glam. Red lights drape the low ceiling; pictures of dead musicians are tacked to the walls. Red, the owner who wears a ball cap and dark sunglasses, sits like a boss behind the bar the entire night. He has style, I can tell.

I ordered a beer. He fetched it, unhurriedly. Things in these parts follow their own time.

Sitting in that old Juke I was somehow reminded that every culture has its myths and legends. It’s how we tell our stories and arouse that sense of wonder in a dark world full of unanswered questions. There’s an underlying truth to these legends, a symbol to be realized.

The legend of Robert Johnson and his midnight bargain with the devil is no different.

The metaphor, the symbol of the legendary story, signifies a young man’s quest to escape the chains of desolation and to become something, something remarkable.

Johnson mysteriously achieved this noble feat and became the King of the Delta Blues at the cost of soul-surrendering hard work and unyielding grit. And though his life was tragically cut short, his music went on to influence a future generation of musicians that revolutionized American music as we know it today.

The whiskey flowed, and people danced, and the night finally closed in on me. I headed back to my shack. The midnight stars danced in the black sky as the melody of crickets mingled with an old blues song playing in the background. A magical ending to an epic road trip.

As the great Mississippi-born playwright, Tennessee Williams, once reminded us, “Make voyages. Attempt them. There’s nothing else.”

Robert Johnson. Crossroad.